Cyber Israel

ATMZombie: banking trojan in Israeli waters

On November 2015, Kaspersky Lab researchers identified ATMZombie, a banking Trojan that is considered to be the first malware to ever steal money from Israeli banks. It uses insidious injection and other sophisticated and stealthy methods. The first method, dubbed “proxy-changing”, is commonly used for HTTP packets inspections. It involves modifying browser proxy configurations and capturing traffic between a client and a server, acting as Man-In-The-Middle.

On November 2015, Kaspersky Lab researchers identified ATMZombie, a banking Trojan that is considered to be the first malware to ever steal money from Israeli banks. It uses insidious injection and other sophisticated and stealthy methods. The first method, dubbed “proxy-changing”, is commonly used for HTTP packets inspections. It involves modifying browser proxy configurations and capturing traffic between a client and a server, acting as Man-In-The-Middle.

Although this is efficient for testing, streaming bank details isn’t as easy. Banks are using encrypted channels, signed with authorized certificates, to prevent the data from being streamed in clear-text. The attackers, however, realized the missing piece and have since issued a certificate of their own, which is embedded in the dropper and is inserted in the root CA list of common browsers in the victim’s machine.

The method of using a “proxy-changer” Trojan to steal bank credentials has been around since the end of 2005, and is being actively used by Brazilian cybercriminals; however, it wasn’t until 2012 that Kaspersky Lab researchers compiled a full attack analysis. “In Brazil malicious PAC files in Trojan bankers have been increasingly common since 2009, when several families such as Trojan.Win32.ProxyChanger started to force the URLs of PAC files in the browser of infected machines.“, said Fabio Assolini, Senior Security Researcher at GReAT Kaspersky Lab, in his article.

A Kaspersky Lab researcher based in Russia had written about similar Trojan attacking PSB-retail customers, dubbed Tochechnyj Banker. It was even backed by a victim case study, where the victim explains how the crocks fooled him into handing out his credentials.

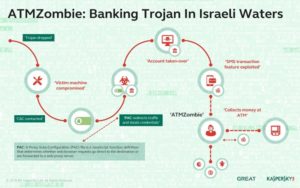

The incident Israeli banks experienced had the same characteristics, but had a very fascinating and innovative method of stealing the money. Instead of relying only on direct wire-transfer or trading credentials, their modus operandi started by leveraging a loophole in one of the bank’s online features; and later by physically withdrawing money from the ATM, assisting money mules (zombies) who are suspected to have no awareness of how the attack works; hence the Trojan was dubbed – ATMZombie.

The threat actor seems to be widely active in banking malware campaigns, as he was found to be registering domains for the following Trojans as well: Corebot, Pkybot and the recent AndroidLocker. However, none uses the same modus operandi. In addition, the actor is being tracked by a number of researchers and also runs rogue online services such as malware encryption and credit card dumps for sale.

Similar to the PSB-retail attack in 2012, the Retefe Banking Trojan, discovered by PaloAlto Networks last August, is quite like a big brother of ATMZombie. It contains an additional Smoke Loader backdoor, which ATMZombie lacks. The other similar banker is that identified by IBM Trusteer’s as Tsukuba.

The proxy configurations file must specifically detail the targets it is aiming at, thus it was fairly easy to spot them. The attack had successfully compromised hundreds of victim machines; however Kaspersky Lab was able to trace only a couple of dozen of them.

Bird view

The Trojan is dropped into the victim machine and starts the unpacking process. Once unpacked it stores certificates in common browsers (Opera, Firefox) and modifies their configurations to match a Man-In-The-Middle attack. It eliminates all possible proxies other than the malware’s and changes cache permissions to read-only. It than continues by changing registry entries with Base64 encoded strings that contain a path to the auto-configuration content (i.e. traffic capture conditions using CAP file syntax) and installs its own signed certificate into the root folder. Later it waits for the victim to login to their bank account and steals their credentials, logs in using their name and exploits the SMS feature to send money to the ATMZombie.

Analysis

After loading the malware executable with your favorite assembler level analysis debugger, it is possible to capture the virtual allocation procedure occurring in run-time. Putting breakpoints in the right instruction points will disclose the unpacked executable. Once the final routine is done, the MZ header will appear in memory. There are many techniques and tools, but this method was enough to unpack the malware.

Looking into the malware assembly code, we were able to identify a number of strings that were embedded in the data section for a reason. The first we spotted was a Base64 string containing a chunk of an outbound communication URL, meant to be embedded in a number of registry entries.

The full report can be found here.